“Everything happens for a reason.”

“I can do anything I set my mind to.”

“People are fundamentally good.”

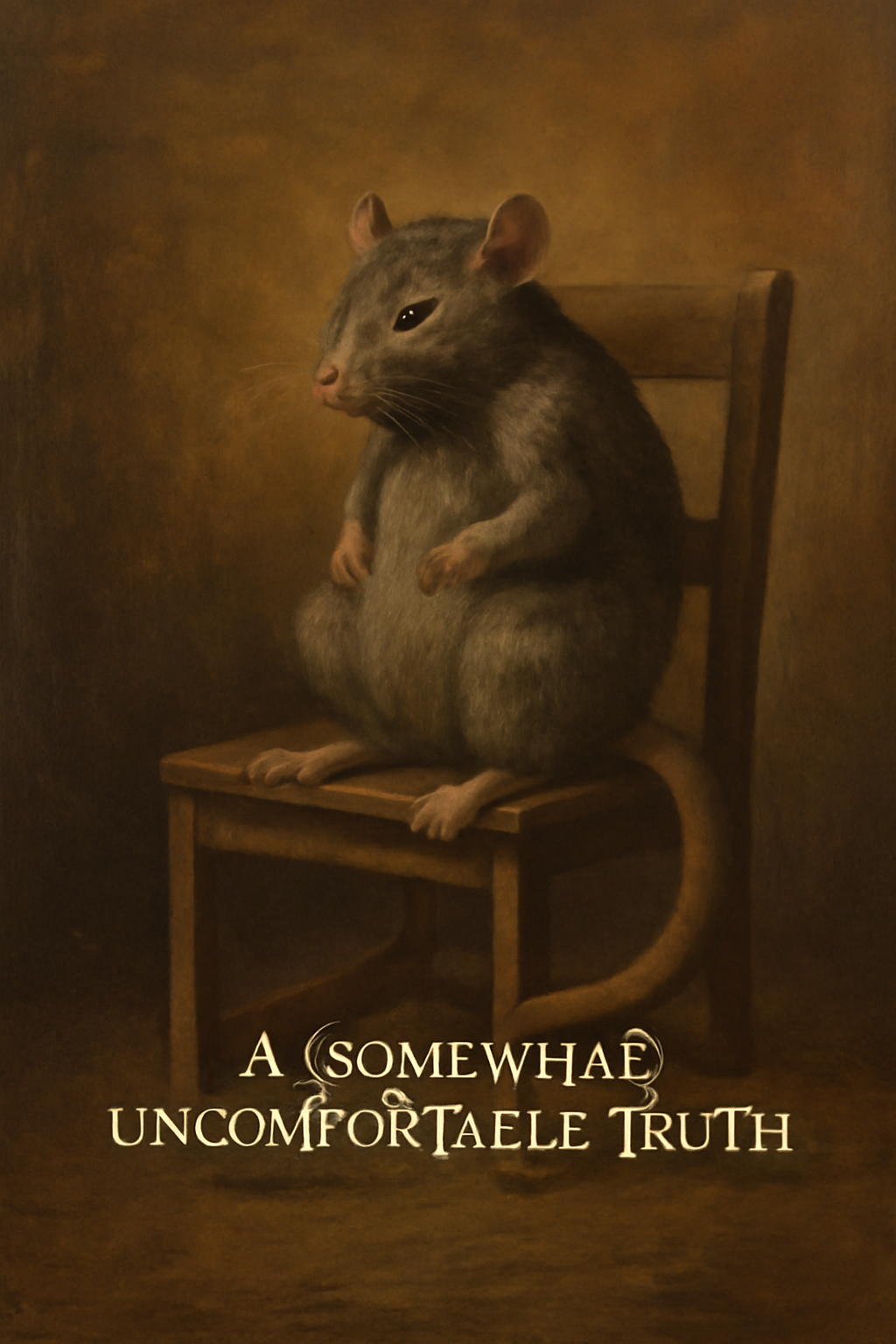

We’ve all heard these phrases — stitched into speeches, passed down through generations, whispered in the dark to calm a storming mind. They’re comforting. Familiar. But are they true?

That’s where things get interesting. Because the value of these ideas doesn’t live in their accuracy. It lives in their effect.

They’re what we might call useful fictions — beliefs we suspect aren’t literally true yet choose to act on as if they were. Hans Vaihinger, a German philosopher, said it plainly: “We know they are false, but we act as if they were true because of their practical utility.”

In other words: the truth of a belief doesn’t always matter as much as what it does to us.

Take “everything happens for a reason.” If you strip it down, the world can feel cruel, random — a game of chance. But wrapped in that belief is a kind of balm: a story that lends suffering some shape. Some meaning. Even if imagined. And often, that imagined meaning is enough to keep us going.

Or consider “I can do anything I set my mind to.” Clearly, that’s not literally true. You can’t think yourself into becoming a concert pianist without ever touching a piano. But the belief itself pulls something powerful to the surface — it invites discipline, action, and hope. That’s the fiction doing its job.

And when we say, “people are fundamentally good”? Maybe we don’t always believe it. But believing it changes how we move through the world. We smile at strangers. We give second chances. We build bridges instead of burning them.

In all these cases, the power isn’t in the facts. It’s in the faith. These stories shape our perception, and through perception, they shape our behaviour. Which means… they shape our lives.

The real brilliance of useful fictions reveals itself when they move beyond individual minds — when they become shared myths, carried across generations, woven into the fabric of entire cultures.

At that scale, they become more than just comforting phrases. They become the scaffolding of civilization.

Free will.

Destined true love.

A final judgment after death.

These are not trivial ideas. They shape laws, shape choices, shape lives. And yet — if we’re honest — they live beyond the reach of proof.

Let’s face it: it’s easier not to look too closely. Easier to let the elephant linger quietly in the room than stare him down. But let’s stare anyway.

Nearly every major belief system teaches that something comes after death — that we are, in some way, judged for how we lived. Objectively speaking, we have no evidence for this. It’s untestable by design.

And yet… that belief makes us more generous. More humble. More kind. And isn’t that, in itself, a kind of truth worth protecting?

Take love. Not the chemical rush of attraction — but the soul-binding conviction that we’re meant to be with someone. Do soulmates exist? Or is it just easier — more beautiful — to believe they do, so that the person beside us feels more like destiny than decision?

Again, the answer may be unknowable. But the effect? Undeniable.

And so, we arrive at something quietly profound:

Some beliefs are worth believing not because they’re true… but because they make truth.

So, what do we do with this?

How do we live, knowing that some of our most sacred beliefs may be illusions — but useful ones?

We choose them, carefully.

We stop chasing certainty and start cultivating meaning. We adopt beliefs that serve us, fortify us, steady us.

Not because they are proven, but because they make life more liveable.

Mine is free will.

I don’t know if it’s real. I don’t know if I’m the author of my thoughts or just the narrator.

Maybe every choice I’ve made was shaped long before I arrived at the crossroads.

But I choose to believe in free will.

Because that belief calls me forward.

It invites effort. It demands courage. It dares me to act.

And maybe that’s the point.

Even if free will is an illusion — it’s a powerful one.

And sometimes, the illusions we choose are the most honest thing about us.